She was also baptized as a Christian not very long ago, and posted it on social media. I found this largely unsurprising. Despite her appearance and previous lifestyle, she has always struck me as having a kind and loving heart and a real passion for helping people. She loves her parents and she loves her clients and co-workers and friends. She was "living the life" before her conversion, despite her many sins, in many ways more so than some who bore the name of Christ long before she did. She, at least, wore her sins on her sleeve. We tend to hide ours with pretense and self-righteousness, and then lecture to others based on superficial nonsense.

I generally dislike pop-culture Christianity, and I don't like the practice of taking popular figures and blowing their conversion stories out of proportion. In general, I wouldn't write about a Baptist Christian's conversion on an Orthodox Christian blog, not because I have anything against Baptists (most of my family is still Baptist), but because it doesn't really fit here. In this case, however, there are several things about her story that I find compelling.

Kat, whose actual name is Katherine von Drachenberg, was raised by Christian missionaries, but left the faith, more or less, as a teenager, around the time she began tattooing and also drinking. She ran away from home and then was sent to a couple of homes that were sort of "scared straight" type places. She did not have kind words for them in this interview. In fact, she suggested they should be illegal, and that she witnessed abuse there. She talked a lot about her upbringing and the fact that she abandoned the faith not because she was driven away, but rather because she had questions and her parents and other authority figures did not have answers for her. But it was obvious being sent to a couple of group homes to "straighten her out" really did more harm than good.

She talked about the impact of fame on her life, of seeking out tattooing because it was a way to meld her artistic talent with her love of helping people. She talked about the negative impact of addiction and her lifestyle on her personal life, overcoming addiction, and then eventually making her way back to God.

Some of the most fascinating parts of the interview dealt with her conversion story itself, and how it was received not only by her non-Christian fans, but also by Christians who responded to her. Her strongest criticism was of the Christians, and hearing her tell her story, I can see why. She talked about self-righteousness, smugness, and the holier-than-thou attitudes of some of the respondents. Many of them criticized her for being insincere and engaging in a publicity stunt. Some criticized those who celebrated her baptism -- in the church building -- as looking like witches. She spoke specifically about people who commented that they will not believe in the sincerity of her conversion until it "bore fruit," which apparently should include a change in her appearance. And on the opposite side, she spoke of how her journey back to Christ included the influence of two men -- Marilyn Manson and Alice Cooper -- who a lot of Christians might think demonic, simply because of the way they look. This even though Alice Cooper has been a Christian for a long, long time at this point.

Another interesting line of discussion was the fact that she appreciates the concept of sacred space, and does not want to go to church to see a concert or performance. She thinks the music in church ought to be set aside for that purpose. She doesn't judge those who think differently, but it's interesting to see someone so new to the faith embrace the idea that worship ought to be worshipful. She also spoke about this from the opposite perspective. She said she doesn't think being a Christian means she has to stop listening to The Cure or Depeche Mode, although she did say her faith now influences the type of music she makes and listens to, and has also influenced her husband, a musician, in a similar way.

She talked a lot about the difference between New Age "seekers" and truly demonic practices, emphasizing that while she wanted to get rid of her books on Tarot and spells and meditation and the like, it was more because she saw them as crutches, or as she later put it, "band aids on a sinking ship." They gave her some temporary relief, but were never life-changing in the way her conversion to Christ was.

There were a few main points of emphasis that I took away from this interview, which I think are pertinent to the Christian faith in general, and to Orthodox Christianity in particular.

She spoke a lot about not being a stumbling block to people who are different, or struggling. One can easily see someone who looks like her walking into a church and being received coldly. Thankfully, she was not. But she spoke a lot about the fact that we cannot know where someone is in their journey, and that superficial judgment can drive people away from the faith. She emphasized that outward appearance, or even just being different, tends to invite judgment, and she specifically spoke about instances where Christians had spoke about her poorly or treated her poorly.

She talked about how despite her departure from the faith for a long time, the seeds were sown in her childhood, and it was those seeds that brought her back. Her parents' lack of judgment, and obvious love for her, ultimately allowed her to return to the faith of her childhood. As parents, we never know how our children will fare once we let them loose into the world. But we can teach them well, and pray for them, and love them. And sometimes, it is that faith and love that ends up paving the way for their return to Christ.

She discussed how she deals with people who attack her, and this was perhaps the most interesting part. She sees a cultural sickness, especially on social media, where people have a zeal to try to "pick apart" (her words) others, to criticize them and drag them down. And she said at one point, instead of doing that "I wish people would just pray for them." She also mentioned having friends who are still addicts and prostitutes and have troubled marriages and so forth, and how she will not abandon them now that she is a Christian. She simply loves and prays for them.

She talked about the historical proofs for Christianity, and the fact that there were, in fact, answers to the questions she had. I found this particularly fascinating since it is Christian history that ultimately led me to the Orthodox Church.

She seemed perturbed that some people called her a "baby Christian." I think this is because it was given to her as a pejorative. And that is tragic. Everyone was at some point a "baby Christian." And many Christians who have been Christians for decades have a superficial understanding of the faith. Kat Von D is a baby Christian, for sure, but there is no shame in that. She said in this interview she did not see her zeal ever waning (the byline in the video is "I'm on fire for Jesus" after all). But it might. As baby Christians, everything is new and exciting and there is so much to learn and explore. Christianity on the ground is messier than that, and it can be discouraging, overwhelming, and depressing at times. So while I hope her zeal never wanes, if it does, it will be the encouragement and love of her fellow Christians that will bring her through it. More to the point, if it does, having a bunch of online Christian nannies saying "I told you so" will only drive her away, maybe for good this time. This is one reason I tend to dislike overinflating the conversion stories of the famous. They might disappoint us, and in our disappointment, we might be tempted to forget that it was love that drew her in, and only love that will see her through tough times.

And that is probably the main takeaway from this interview that I think is instructive to us Orthodox Christians today. Kat Von D is the opposite of a poster child for what most people think a Christian should look like, or even be like. But despite that, she has love, and she seeks only love. There is a lot of talk of late about the newly coined concept of "othering." Meaning, we treat people like they are not one of us, often superficially. But this has no place in the Christian Church. I recently ran across a quote from Fr. Thomas Hopko that is on point here:

"Now some kinda fancy thinkers like to think things, and say: 'Oh, well, people are sinners, but you love Christ in that person, you love the Image of God in that person.' Well baloney! Jesus didn't say 'love the Image of God in that person.' He didn't say 'love Me in that person.' He said: 'love that person, and you will be loving Me. Because I have identified with every human being on the face of the earth. Everyone, whoever they are.'"

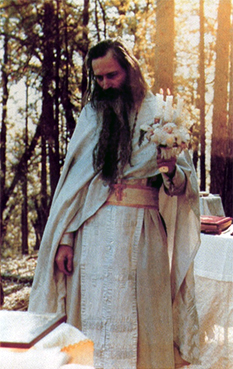

Father Tom was the Dean Emeritus of St. Vladimir Orthodox seminary, a learned man, well credentialed, who looked exactly like you would expect a Christian to look, and who is beloved of Orthodox Christians the world over. It is worth noting that a "baby Christian" covered in tattoos who dresses in black and wears white makeup on her face and wears bright red lipstick and has lived a hard and at times overtly sinful life came to the same conclusion he did. Glory to God.